In 1780 the British repeated their assault on Charles Town. As they did the previous year, they marched through the heart of St. Andrew’s Parish, but this time threatened the church. British General Sir Henry Clinton sailed from New York in December 1779 and landed at Simmons (Seabrook) Island on February 11, 1780. The British advanced up Johns Island to Stono Ferry, then across to James Island later that month, capturing Fort Johnson. In early March the British crossed Wappoo Creek. Johann Ewald, a captain in the elite Hessian Jäger troops fighting alongside the British, was part of the assault. The diary he kept during the war included a detailed record of his foray into St. Andrew’s Parish.

Captain Ewald found it a forbidding place. Wolves, snakes, and poisonous insects were everywhere. Soldiers tried to keep them at bay by lighting large fires at night. They discovered alligators ten to twelve feet long in a marshy pond that connected to Wappoo Creek. At daybreak on March 15, 1780, more than 500 British soldiers set out on a foraging expedition. As they approached the parish church, which was situated in the midst of rice fields, they discovered that Continental troops had destroyed the bridge over Coppain Creek. The insurgents had positioned themselves along the north side of the creek and began to fire on the advancing British. Three days later a Prussian deserter from the American troops stationed at the church warned Ewald that patriot cavalry would soon launch an attack on the Hessians. On the twenty-first, Ewald heard that Gen. Lincoln and 7,000 men had taken refuge in Charles Town, leaving Ashley Ferry with only a “warning detachment.”

On the afternoon of March 22, the British and Hessians again advanced toward the church. Cannon fire erupted on the north side of the creek. British General Alexander Leslie asked Ewald if he would mount an attack away from the main action further up the creek. “If not,” Ewald recounted, “cannon must be brought up.” Ewald accepted the challenge, and his decision spared the church from possible destruction. At 7:00 p.m. he and his men crossed the shallow creek, but the swamp he found on the other side (“a good half hour wide”) was “so muddy and deep that many of our men sank in up to their chests.” With the Hessians struggling in the swamp, the patriots fled. “We quickly took post in the churchyard,” Ewald said, “and began work on the bridge at once.”

—————

No parish suffered like St. Andrew’s. “The ravages of war have left St. Andrew’s a desolation,” Rev. Drayton reported in 1866. “But one dwelling has survived [Drayton Hall], exclusive of the parsonage. All are in ashes.” Although the church was in one piece, Drayton did not know when the church could be opened for services. He had not been able to visit his parish, since both its bridges had been burned. A diocesan report on the destruction of churches painted a grim picture.

ST. ANDREW’S PARISH.—This venerable Church, built in 1706, survives—but in the midst of a desert. Every residence but one, on the west bank of Ashley River, was burnt simultaneously with the evacuation of Charleston, by the besieging forces from James Island. Many of these were historical homes in South Carolina; the abodes of refinement and hospitality for more than a century past. The residence of the Rector was embowered in one of the most beautiful gardens which nature and art can create—more than two hundred varieties of camelia, combined with stately avenues of magnolia, to delight the eye of even European visitors. But not a vestige remains, save the ruins of his ancestral home [Magnolia-on-the-Ashley].

The demon of civil war was let loose in this Parish. But three residences exist in the whole space between the Ashley and Stono rivers. Fire and sword were not enough. Family vaults were rifled, and the coffins of the dead forced open in pursuit of plunder.

It must be many years before the congregation can return in sufficient numbers to rebuild their homes and restore the worship of God.

—————

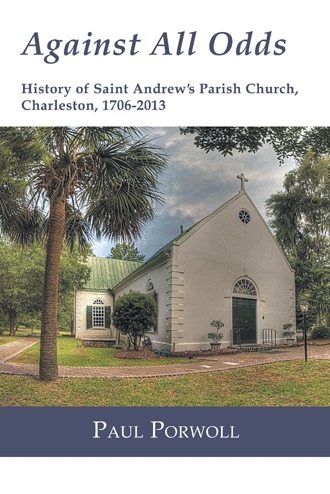

Reopening the mother church in 1948 was no easy decision. It was located nearly at the end of civilization, a long commute and the last stop before striking out on the long road to the Ashley River plantations. Driving time aside, the condition of the church was dreadful. “You can imagine how our hearts fell when we went out to inspect the grounds and building,” wrote Mrs. Gene Taylor, one of the early members who became parish historian and a tireless promoter of the church. “A veritable forest surrounded the church, and plaster was hanging from every side, and remember, there were only a very, very few of us, none with fat bank accounts.” Parishioners and clergy took a deep breath and plunged forward. They entered the future by restoring the past.