Tohil stood silently, head down, arms limp, feet shuffling. Showing affection was difficult for him in full view of other Mayans. He looked into the face of his wife, Yatzil, as he gently helped her off their donkey. Her eyes revealed both tenderness and foreboding. Understanding each, he turned and motioned toward the village.

“Stay here until I return. I will go back and gather what I can. I’ll bring the donkey with me. Now rest, this day has been hard on you.” He placed his hand on her swollen abdomen and added, “And on our child.” Tears fell from Yatzil’s eyes.

“If he is a boy, we will name him after the god of thunder,” he said looking over his shoulder at the gathering gloom. “If the baby is a girl, we will call her Itzal, Rainbow Woman.”

Several weeks ago, the mountain had shown signs of change, but Tohil and Yatzil living on its flank did not know how to interpret them. It wasn’t until the birds had all flown away that they experienced fear. Tohil was oblivious to the changes taking place deep in the mountain and could not have known what was soon to happen.

Staring again at the mountain towering behind him, he shook his head and said, “No, continue moving with the others. Do not stop here. I will return and find you at another village further along. Now go. We have no more time.” He left her there on the road with the others. She remained still, watching him go until he was out of sight.

Hours later he entered their humble shelter and grabbed all he thought important, tying most of it on his donkey and leaving some for himself to carry. Looking around one last time at the home he had worked so hard to build, Tohil turned and began to run back down the path.

His wiry legs churned rapidly. Looking back, then forward and back again, Tohil could move no faster; he was burdened by the heavy load on his back. His right hand grasped his donkey’s reins. She too was burdened down but ran at a near gallop, eyes wild with ears pulled back. He feared that returning for a few meager things had been foolish and that he had stayed too long.

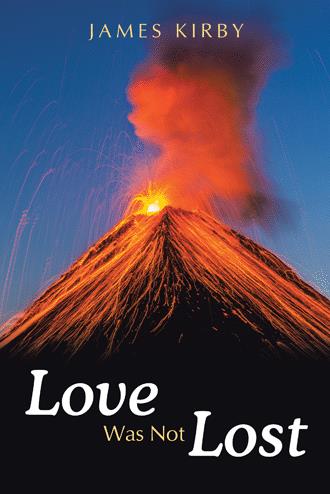

Enormous pressure was forcing molten rock below the earth’s mantle upward, searching for an escape. The volcano Fuego was a vent and would provide that relief as it had done many times through millenniums. The upward thrust produced no earthquakes, except for a few tremors that the villagers thought commonplace.

On the morning of December 2, 1867, a surge of molten rock reached vast caches of hidden water which had collected within the mountain from decades of rain. The bottom of the volcano’s caldera, nearly a perfect circle, was a plug of lava laying in the base of a crater left by the last eruption fifty-seven years before. A shallow, serene lake hid all evidence of this plug, belying the danger it caused. The surge slowed, the plug having briefly held the lava’s upward motion in check, and the stalled molten rock turned the hidden water into pressurized super-heated steam. A booming eruption took Tohil by surprise; the caldera plug could no longer hold the pressure. Tohil’s breathing was labored; he ran at a steady but frantic pace. Then the donkey took the lead, dragging Tohil along.

With several more deafening booms a tightly compressed mass of volcanic gases and super-heated steam blasted through Fuego’s clogged throat giving violent and destructive life to the mountain once again. A horrendous sound and the hideous stench of burning sulfur escaped from the caldera followed by a massive cloud of smoke. Small rocks, pumice, and ash were viciously propelled into the sky by the foul gases and steam. In the early morning light this pillar of cloud looked both terrifying in power and awesome in beauty. It reached higher with each second in a rolling, boiling motion, twisting and turning as it grew more menacing and deadly. Soon, boulder sized projectiles, hurled aloft by the initial explosion, pummeled the land like a volley of artillery shells. The pillar continued to rise higher with an anger and arrogance as if to challenge the very gates of heaven. Then, when it had reached nearly five miles into the sky, the pillar of cloud began to collapse in upon itself, a victim of its own dense weight. Exhausted and terrified, Tohil stumbled and fell on his face. His hand lost grasp of the reins and the donkey broke away.

The destruction grew in two directions. The collapsing cloud of pumice and ash dropped back down dragging with it the gases still issuing from its throat in and giving birth to a pyroclastic flow. Gathering speed until it reached 220 miles per hour and following the shape of the volcano, the flow raced downward, crashing, churning, devouring, utterly destroying everything in its path. No building survived; no tree was left standing. The sound was deafening. Temperatures at the leading edge of the flow were nearly three hundred degrees. What was not instantly burned up was obliterated by the rocks and debris hurtling along at blinding speeds. Tohil and his donkey were instantly asphyxiated then vaporized, never knowing what hit them. Below, the pyroclastic flow brought instant destruction. Above, the cloud carried a slower death.

The pillar of light ash and smoke continued its ascent until it reached an altitude of nearly eight miles. Winds blew the column toward Lake Atitlán, twenty-five miles away. Ash and debris fell along the way covering the ground like a carpet two to three feet thick, collapsing roofs, killing livestock and destroying all crops and plants in its path. It blanketed the ground in death.

In time the land would heal, the fertile ground would burst forth once again with life, and the region would become one of the premier coffee growing areas of Central America.