Flora stood by her kitchen window and watched the children gathering in the distance. The iron gate was locked nightly, securing the walled compound around the church and mission house. Jon, her preacher husband, had designed the perfectly square mission compound on a paper napkin in a local café one Saturday afternoon, shortly after their arrival in the bustling Brazilian city. The cinder block church squatted and tanned in the far corner. Its hollow wooden steeple was washed in white, towering in glaring contrast.

“A bell. It needs a bell,” said Susan, during a breakfast of grits and eggs. “How else will the people know when to come?”

She had a point. The Crow family’s adopted land didn’t seem to be constrained by clocks and watches and other conveniences that spoke of changing time and seasons. So requests were made, and children from their home state of Alabama took on the charge. After no time at all, the children had gathered enough coins and paper bills to purchase a bell. Dressed in taffeta and white stockings, bow ties and suspenders, the Sunday school class presented their offering one Easter morning in early spring. Enveloped in a bubble-wrapped cocoon, the bell arrived unscathed.

Photos of the Easter-morning service where the children had presented their offerings were included with the brass bell. The children stood shining, polished, tall, and proud. The stark contrast of worlds was not lost on any of the family. Even Susan, whose feet had only touched America’s soil a scant few times, and who knew of another world of fancy and ruffles, spun around as normal as could be.

Grateful for the gift and compelled to see it to completion, Jon cut a hole through the peak of the steeple and built a brace on which to hang the bell and its frame. He threaded a rope through the pulley and let it drop down through the center of the steeple until it hit the floor of the church. Now, the ringing of the bell marked the beginning and ending of each day, and it punctuated the Sabbath with an extra burst of joy.

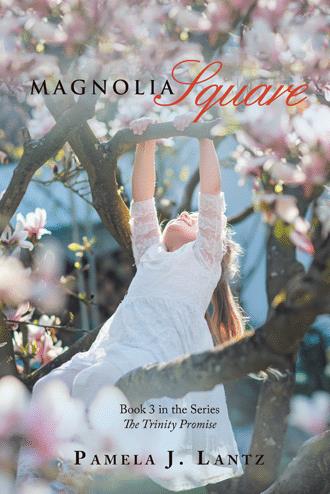

Jon’s concern for his family was the reason for the solid concrete block wall that surrounded the mission compound. It consisted of one square acre and had been aptly named Magnolia Square, for the white-flowered and waxy-leaved magnolia trees that lined the streets and offered intermittent shade over the mission house, church, and surrounding land. The locked iron gates were to protect his family, yet their forbidding appearance still troubled him. He was not trying to keep people away—certainly not. Most people anyway. Unfortunately, just the mere fact that they were Americans and the assumption that they were wealthy because of their land of origin marked them as targets for thieves and dangerous sorts.

He had hired a local crew to plant flowering vines and bushes to soften the edges. He had also planted rows of greens, peppers, tomatoes, tomatillos, and squash outside Magnolia Square’s gate, free for the picking. Mango and avocado trees stood opposite the magnolia trees. The trees’ fruit had become equal parts food and weapons as the children often pummeled one another or a passerby.

Flora planted colorful succulents, cacti, vegetables, and greens in a corner of the backyard, for both beauty and function. The raised garden beds resembled framed quilts, composted and fitted with soaking hoses in order to ensure a harvest even through the harshest of summers. There she would prod greens with fish emulsion and cover them with canopies in the heat of the day. Tomatoes, peppers, corn, sweet peas, onions, and summer and winter squash tendrilled up trellises and over fences.

Jon hung a tire swing and built a playground on the grounds between their home and the church. Woven grass mats sat under palms, where daily the children would sit and listen to teachers speak of letters and numbers and of angels that rode on the currents from blowing winds.

This was home. They tended to its square borders and lovely people as best they could. Some funds were certain, as they had been set by the mission board. Other resources came through letter campaigns and fundraisers. But for Jon and Flora, this was not enough. Just caring for their own needs was not why they had come to Belem. They could do that anywhere. No, they had to establish themselves as working people, creating their own income and teaching others to do the same.

They needed to immerse themselves in the culture and community, making friends with leaders, politicians, local school officials, and police. It took some time, but through the years, the tall, fair-skinned couple learned perfect Portuguese and could throw down an authentic meal cooked straight from their own garden, just like their neighbors.

The throngs of flies that hung on strings of fish and slabs of meat in the outdoor market hardly bothered Flora anymore. “Enough heat in the oven and pan will kill any germ that tries to tag along,” she would say as she carefully washed all produce purchased from the market-stall vendors. She had also learned to gather corn and flour from the middle of the market’s sacks of grains. She had learned to strategically drop purchases on her walk home, not wanting to cater to the beggars, for her safety, but wanting to contribute to the beggars just the same.

Flora and her girls could cook a traditional seafood stew without a second thought, even impressing other women who came to work at the mission. Flan was a family favorite and always the dessert of choice when they entertained, served with strong coffee flavored with sweetened, condensed milk that had been boiled right in the can.

The familiar ache in Flora’s heart returned as she placed the last breakfast dish in the cupboard. She ran her fingers over embroidered magnolias before hanging the dish towel to dry over a wooden dowel rod. She laughed at the irony of it all. A true southerner trained in the domestic arts sent to the slums of Brazil. When she took her marital vows, she had meant them with all her heart. “Where you go, I will go and will serve the Lord faithfully all the days of my life.”